Dreams and risks

When a new company gets started, there’s usually some big dream in mind. “Open a 5 star resort on the moon!” “Make a brain implant that teaches dogs to talk!”. Dream big, folks.

That destination is just that, though: a destination. There are a whole slew of hurdles that stand in the way of that company and its dazzling future. If you’re evaluating the merit of investing your time or money in a company, it’s often useful to ask yourself “What things do I need to believe in order for this investment (of time or money) to not make me look like a big fat idiot in the future?”

Take Google, for example. When they were grad students at Stanford, Larry Page and Sergey Brin codeveloped the PageRank algorithm to better rank search results on the internet, eventually dropping out to found Google. In order to believe that PageRank could form the basis of a successful company, you had to believe:

- The algorithm generated meaningfully better search results than the existing search engines could

- The algorithm could actually be implemented and run at “web scale”. (Admittedly a lot smaller in 1998 than today.)

- The algorithm wouldn’t just be copied by the existing search engines behemoths like Yahoo or Alta Vista. (Thankfully, a patent on the algorithm helped out here.)

- More and more people would use Google because it was a better search engine

- That better search engine could be successfully monetized and turned into a good business

- The money generated from successful monetization and the data generated from increased usage of the search engine could then be used to produce a meaningfully better search engine, feeding back into step 5 categories:

If you’re starting a company, there’s a good chance that you need to get buy-in from both potential hires and potential investors. Coming up with an accurate list of “beliefs” or “hypotheses” to be tested is a great first step towards getting that buy-in: it at least shows others that you’re realistic about the challenges you face.

If you have some pedigree, a cofounder, a decent tech-enabled business idea, a vague notion of how to bring that idea to fruition, and the knowhow to pitch that idea, then your company is probably worth on the order of a couple hundred thousand dollars these days. Congratulations!

However, maybe more importantly, you now have some very concrete steps to increase that valuation. The reason that your company is worth what it is instead of the gazillion dollars that it would be worth if all those hypotheses were true is that the company’s value is discounted to account for the key risks you face.

To increase your valuation, you just have to take the easiest hypothesis to test and prove it. Going back to the Google example, if Larry and Sergey indexed a single “segment” of the web like stanford.edu, they have the opportunity to reduce the risk for two of the hypotheses:

- They proved they have the know-how to build a version of Google that runs at sub-web scale

- They can do some very basic testing where they ask 20 people which search results they prefer for a Stanford-related query, Google or Alta Vista?

This certainly doesn’t guarantee the success of their company, but it’s likely enough to drive up their valuation significantly - say, from $200,000 to $1 million.

With that higher valuation, they can seek outside investment in their company, selling 20% of the company to raise $200,000.

With those funds, they could:

- Acquire additional hardware, prove that the algorithm can work at web scale, and release a beta version of the search engine

- Hire a patent attorney to help them file for a patent on their algorithm

… and now the company is really off and running. They’ve greatly reduced or eliminated many of the early-stage existential risks to the company (hypotheses 1-3) and are in a great position to test their growth strategy (hypothesis 4).

They’ve also provided enough signal to unlock a new tier of investors and early-stage employees by demonstrating that the company has a real shot at success: it wouldn’t be stretch to say that nowadays such a company might be able to raise $10 million in funding. The later hypotheses are obvious harder to test, but thankfully the company has more human and capital resources at its disposal to test them. It can now sell the same portion of the company that it sold before (20%) but for much more money ($2 million instead of $200,000).

With that capital, they can hire someone with better knowledge of how advertisers allocate their resources and build an effective advertising business to help them monetize searches. They can also hire someone knowledgeable about growing startups to help identify obstacles that are hindering growth.

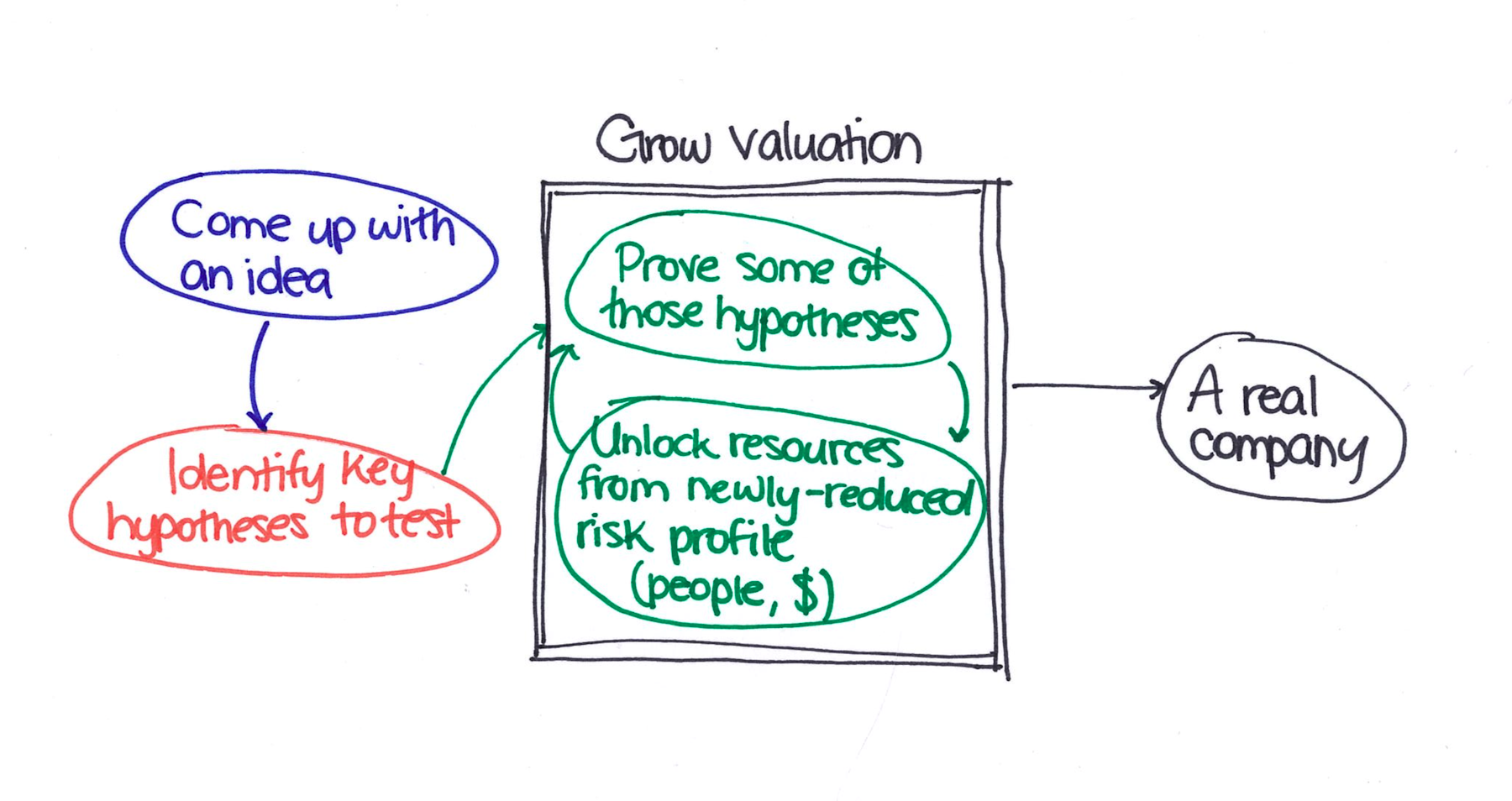

In the end, this method of company building looks a little like this:

One of the reasons that this framework is effective is that there’s often a gaping chasm between “What’s the next easiest hypothesis to test?” and “What should I do next that makes this company look more like a real company?”. Early-stage investors tend to care a lot more about the former than the latter: “making a company look real” by renting an office and paying for health insurance is easy given sufficient resources, but you’ll inevitably run aground if you try to scale a company built on flawed underpinnings.

Another reason that this framework is effective is that investors always want to know “Why is this money going to help you succeed?”. This plan ensures you have a clear answer: “file for a patent”, “buy hardware to bring our prototype from Stanford-scale to web-scale”, etc.

By systematically identifying the hypotheses that underpin your company, proving those hypotheses, and leveraging the resources unlocked from that newly reduced risk profile, you should hopefully be able to build that 5 star resort on the moon while not looking like a big fat idiot. Happy launch day!