How employees can get burned in acquisitions

Back in November, another company seriously considered acquiring our startup. As the CTO, I was thoroughly grilled about all of our technical assets and liabilities.

The most prominent lesson I took away was “nothing is real until the ink is dry”: the cash offer for the acquisition was withdrawn about three weeks after it was verbally made. Overnight, we went from adjusting spreadsheet numbers in search of an equitable split to discussing our favorite flavors of ramen.

My second biggest lesson was that I should never, ever work at or invest in a startup where I don’t trust the executives – even if others urge that doing so might make me fistfuls of cash. There are too many opportunities for bad execs to burn just about anyone that touches their startup.

Thankfully, this wasn’t a concern this time around: I trust Curtis Wiklund (the founder of Channels) immensely and he repeatedly proved worthy of that trust. However, it seems worth sharing some ways I learned that you can be burned as an employee during an acquisition.

Acquisitions are typically announced in the press with headlines like “Dropbox sells for $50 billion”. The reality is more complicated.

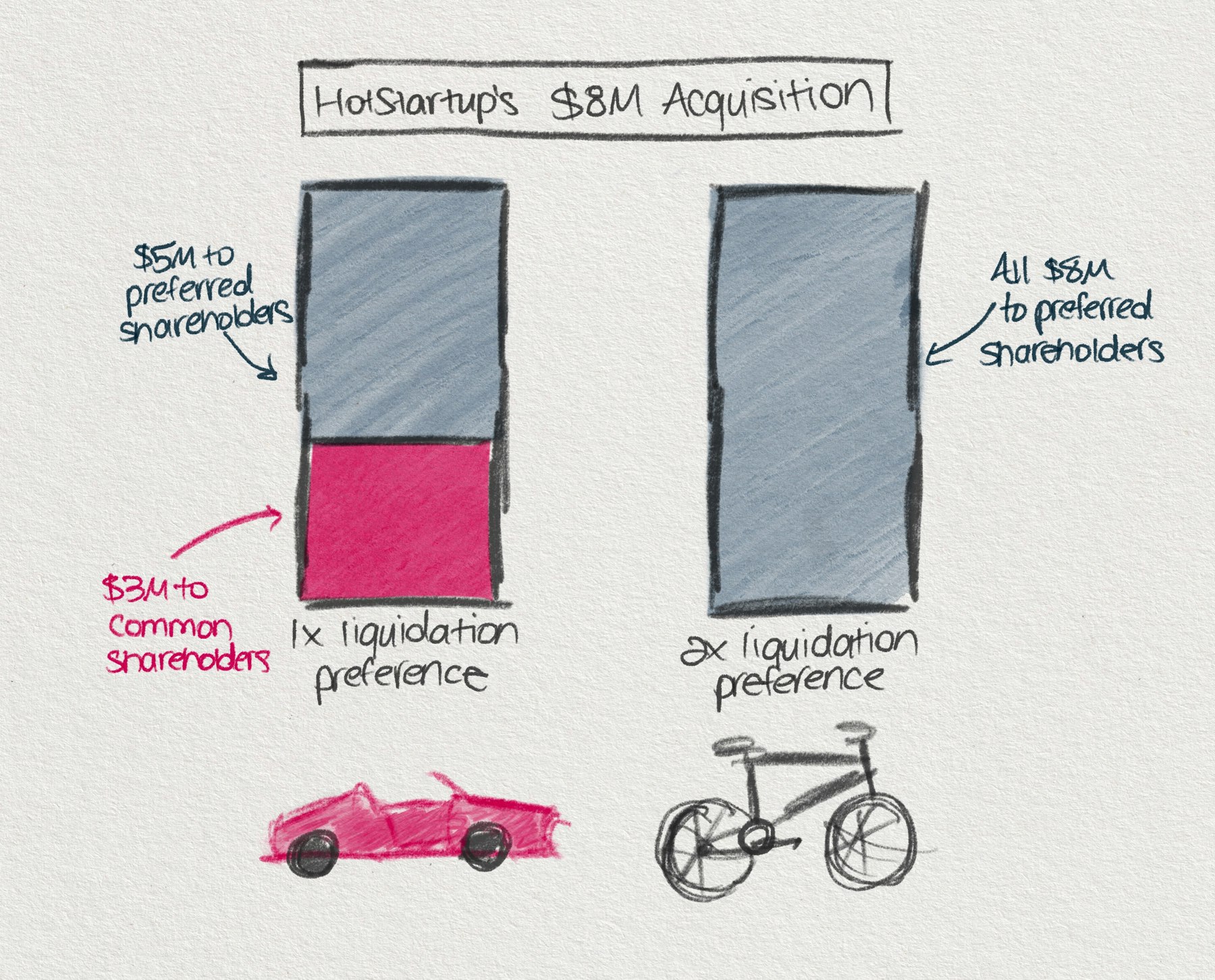

For illustrative purposes, let’s consider a fictional HotStartup that raised $5M. Let’s say that this money was raised by selling 20% of the company in a single round of financing, placing the post-money valuation of the company at $25M.

Those cash investors are almost always given preferred shares in the company. This is in contrast with the common shares given to employees in the form of stock options.

Those preferred shares also come with a term known as a liquidation preference. This is a multiplier (usually somewhere from 1-2x) that specifies the return that preferred shareholders are entitled to receive before common shareholders receive any money. This is critical: in the event of an acquisition, investors’ cash is valued above employees’ work.

Preferred shareholders also reserve the right to convert their preferred stock to common stock, forgoing their liquidation preference. You can expect them to do so if it’s beneficial to them. If an investor invested $1M at a 1x liquidation preference and received 10% of the company, then they’ll keep their preferred shares with the liquidation preference unless the exit is for more than $10M, at which point they’ll convert their preferred stock to common and instead take 10% of the acquisition amount.

Particularly for small acquisitions, liquidation preferences play an outsized role in determining how much money flows through to common shareholders and therefore how much employees (the common shareholders) get paid. Compare the following two outcomes for our hypothetical acquisition with different liquidation preferences:

In the first example, a CEO with 50% of common shares rides away in a Ferrari. In the second, they ride away on their rusty Huffy bike.

Astute readers will notice that while a liquidation preference is meant to reduce risk for investors, it can also skew incentives in a way that hurts those same investors. In the above scenario where common shareholders receive no money from the acquisition, why on Earth would the executives from the company pursue that acquisition? The startup is sitting on an asset potentially worth millions of dollars with literally no incentive to sell that asset. Acquisitions require tons of work and stress: furthermore, they often require the executive team from HotStartup to work at the likely-not-very-entrepeneurial AcquiringCo for a year or more after the acquisition (via lock-up agreements).

The executives at HotStartup have two main ways to resolve this incentive misalignment:

- They can renegotiate the liquidation preference so that more of the acquisition proceeds flow through to common shareholders, of which they presumably own lots

- They can request a management pool be allocated to key executives responsible for the acquisition. This is basically a bonus pool paid out to the executives before any preferred or common shareholders are compensated for their stock.

Any agreement needs to be approved by the board (or investors if no board exists), but the board is often faced with a “take it or leave it” offer. This is particularly true at low exit prices where the company might otherwise just shut down.

Management pools may seem borderline ethical at first glance, but they can make a lot of sense. Much of our acquisition’s value hinged on the tech transfer, which in turn depended heavily on me as CTO. Because of this, I’d be required to sign a lock-up agreement. However, I didn’t hold nearly enough common shares to have the acquisition outweigh my “next best alternative” (going to work at another company). A management pool could help bring those two in line so that an acquisition was as beneficial to me as it was to the other stakeholders.

The last lever available in the offer is the team’s compensation package at AcquiringCo after the acquisition. An acquirer could save money by making a lowball offer for HotStartup with an overly-generous salary for the CEO once he’s at AcquiringCo. This is effectively bribing the decision maker to reduce the payout to the other stakeholders. In this situation, the burden is on the CEO to negotiate for a larger acquisition price for all shareholders, even knowing that it may mean less total compensation for themself.

To be clear: management pools, generous executive compensation packages, and renegotiation of liquidation preferences can all be useful tools in structuring acquisitions. The goal is to reach an overall package where everyone feels that the acquisition is worth the opportunity cost.

However, particularly in “middling outcome acquisitions”, there’s often not enough pie to go around for everyone to get fat. Because executives wield most of the decision-making power in these negotiations, they’ll have every opportunity to push the acquisition in extreme directions that benefit themselves and hurt employees.

Specifically, they can:

- Negotiate with the board for an outsized management pool instead of a lower liquidation preference knowing that the management pool impacts their compensation disproportionately (hurting employees)

- Negotiate with AcquiringCo for a lower acquisition price in exchange for a higher compensation package post-acquisition (hurting both investors and employees)

In these acquisitions, liquidation preferences play an outsized role. Because of this, it’s worth asking about the liquidation preferences for current investors when joining a startup. Furthermore, it’s critical when joining a startup that you have faith in the leadership team: upon an exit, they’ll have every opportunity to burn you.

If you’re interested in learning more, I’d heartily recommend reading The Holloway Guide to Equity Compensation. The Long-Term Stock Exchange also has an excellent article on liquidation preferences. I read most of the former when I first joined Channels and what I learned proved invaluable over the past few months.