Becoming an expert #2: the learning cycle

When you start out at anything, you’re probably really bad. Some people aren’t, but those people are annoying so we’ll ignore them.

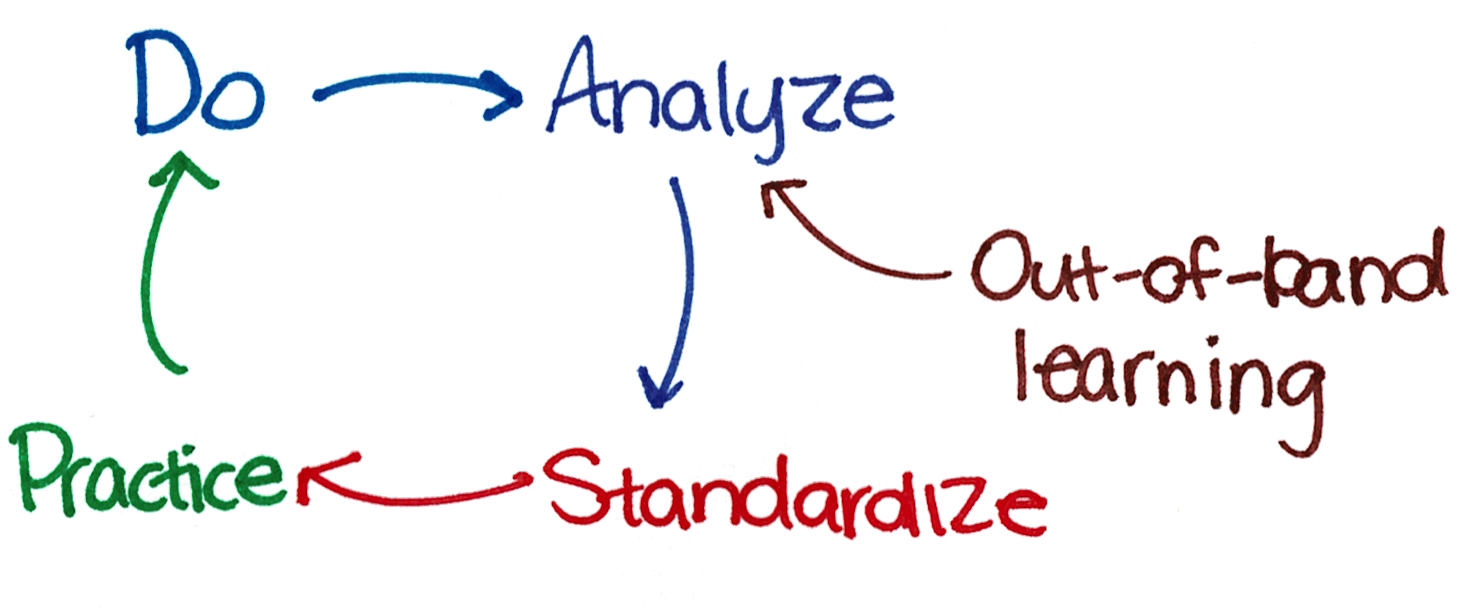

Across most activities, we see the same cycle play out as people learn:

Let’s quickly zoom in on each step.

Do

This one’s pretty obvious: you do the thing that you’re trying to get good at. If you’re like me, you probably start out doing something poorly, but hey, ya got out there kiddo and I’m proud of you.

It’s important while “doing” to find some way to record a transcript of what really happened - a video recording, audio recording, or whatever other format you need to get a ground truth account of what really transpired here. We’ll use this to…

Analyze

This is where I - and many people - fall off the bandwagon.

In this phase, we look back at our “ground truth” with two goals in mind:

- To compare how we performed against some standards that we’ve set for ourselves and see how the two compare. (We’ll get to that in a second. For now, let’s assume you have no standards)

- To look for big problems in our “doing” where, even if we met our existing standards perfectly, we’d still have performed poorly. We’ll use those to revise and build our standards in the next step.

What we’re really looking for here is eureka moments where we see that problems we run into - that can feel unavoidable at the time - are often the result of earlier fixable mistakes.

Standardize

In this step, we take what we learned from our analysis and encode it into some sort of realistic ruleset that we can hold ourselves against in the future.

“Realistic” means that there can’t be a bajillion items on this list: at most you should be adding one or two items from each analysis section. Better still is if you can revise an existing rule to be more accurate.

Practice

The goal with practice is to narrow down the “doing” stage as much as possible to focus on getting “reps” in a particular area.

Practice is pretty draining, so I find it really helpful to set a visual timer (I like the Time Timer) for no more than 30 minutes and focus only on what I’m practicing for that time period. After that, I’ll walk away and do something else. If I try to practice for much longer than that, I find that I lose focus and start to fall into my old ruts again. It’s much more important to practice regularly but avoid these ruts than it is to practice for a long time.

… and do again.

With your new standards and skills in hand, it’s time to get back to doing.

This time around, try to approach the “doing” while holding your standards in half of your brain while performing the activity with the other half.

What you’re shooting for here is “marginally better than the last time I did this thing”. No trip through this loop yields significant results, but each leads to a little improvement that compounds over time.

Out-of-band learning

Outside of this loop, it’s sometimes necessary to do some out-of-band learning. This is when you read a book, talk to a coach, take a class, or watch a video.

I usually put too much hope in out-of-band learning. Frankly, if I’m not already doing the things I know I need to be doing, then there’s not a ton of sense in going off and learning new things that I should be doing. And yet.

The main goal of out-of-band learning is to help you improve your analysis skills. If you find yourself frequently unable to diagnose problems in why things went poorly in “doing”, it may be time to hit the books.

One of the hardest things about out-of-band learning is finding the right resources. A book aimed at advanced chess players will be worse-than-useless for beginners: it’ll be discouraging and focus on fine details that won’t really help beginners.

Similarly, I find coaches can sometimes be overly prescriptive or theoretical for my taste.

High quality out-of-band learning resources though can help give you ideas for what and how to practice as well as what themes to look for during analysis.

I don’t have much guidance for how to find good resources - “you’ll know them when you see them”.

The most helpful resource I used while improving at chess was John Bartholomew’s YouTube channel. John has a clear love for the game of chess, has a sense of humor about his mistakes, and is great at identifying unifying themes that span games and are applicable for players of a given level. You can get an idea of his style here.

Yikes! That’s a lot of work.

The main problem with becoming good at something is that it’s hard. That’s why most people just reach a passable competence in most domains and stop progressing.

However, this cycle is significantly more effective than the “do-do-do” cycle that most people use once they reach a basic level of competence.

In the next post, I’ll talk about some techniques that can be useful in sustaining this improvement for the long haul.